The United States Constitution is considered a sacred document in American tradition. It is the compass that directs our ideologies, political debates, and government reforms. For many, the Constitution coincides with the birth of the U.S. and perfectly personifies the spirit that led those “heroic patriots” to independence from the British over 300 years ago. However, our proclivity to revere the Constitution in such a way has shielded us from truly understanding the events that led to its creation.

In the first decade of the United States’ independence, The Articles of Confederation left the country in division, economic recession, and social unrest. This turmoil brought about intense debate regarding the drawing of a new constitution. Its’ main proponents advocated for a constitution that would establish a stronger national government, which could preserve order and promote unification. Their opponents on the other hand were deeply fearful of centralized government and perceived these changes as a return to the tyrannical rule that the colonists faced under the British.

For much of the 1780’s, these two sides clashed passionately about the future of the country. At the peak of this debate, one event struck a chord with the entire country and paved the way for the adoption of the Constitution – Shays’s Rebellion. Starting in 1786, a ragtag group of farmers in western Massachusetts, referring to themselves as “regulators” barnstormed the state, targeting government officials and confronting an apathetic ruling class. Without Shays’s Rebellion and the plight of backcountry farmers in western Massachusetts, it’s possible the Constitution that we as a country so ardently identify with would only remain in the imaginations of America’s greatest political thinkers.

Very little is known about Daniel Shays personal life. Leaving out Shays’s Rebellion, his background is that of a typical farmer in rural Massachusetts…

For the supposed leader of a rebellion that influenced the creation of a document that we still hold true today, it’s surprising that not much is known about Daniel Shays. For one, Shays never posed for an official portrait and the records of those that knew him did not provide sufficient details of his physical appearance, so historians do not have an accurate portrayal of what he looked like. What we do know is that Shays was born in Massachusetts, was recruited into the Massachusetts militia at the start of the Revolutionary War, and eventually rose the ranks to become a sergeant then an officer. After the war, he and his wife Abigail bought a small farm in Pelham, Massachusetts.

For historians that have explored primary accounts of Shays, the evidence is shadowy at best. He was broadly described as brave and earnest by his fellow servicemen in the Revolutionary War and well-regarded by fellow regulators during the rebellion, but not much else has been uncovered. We do know that Shays had accumulated a substantial amount of debt. He was sued by at least two men in Massachusetts for unpaid debt, and records show that at the time of the Rebellion, he was in debt to at least 10 men. His financial situation became so dire that he had to sell off a sword that was given to him as a gift by Marquis de Lafayette, a decision that was later used to disparage his reputation during the rebellion.

These factors and more pushed Shays to join the regulators in 1786, but he was not an instrumental figure in the rebellion from the start. On multiple occasions, he turned down opportunities to lead regiments in court closings. Regardless, by the end of the year Shays had become an active insurgent, commanding the largest regiment of regulators. Although there were several “leaders” of the rebellion at various times – Job Shattuck, Luke Day, and Eli Parsons just to name a few – Shays was the clear scapegoat to government officials and the press. As you will see, Shays is portrayed by those in positions of power as a caricature of the ‘despicable’ rebels they failed to control or empathize with. Because of the propaganda, Shays’s role in the rebellion was inflated in the minds of many, and that misconception had a huge impact on the eventual passage of the Constitution.

The lead up to Shays’s Rebellion highlighted the shortcoming of the local, state, and national government systems in the early United States…

The Articles of Confederation facilitated a national formation of disparate territories – those being the 13 states. Each state had its own trade policies, currency, and governmental system. Among the 13 states, these governmental systems broadly fell into two camps of democracy, direct or representative. The social unrest that led to Shays’s Rebellion was largely a result of the failure of the Articles to unite these two camps.

For example, Pennsylvania’s constitution featured measures that favored direct democracy. Influenced heavily by Thomas Paine, one of the leading patriot voices during the Revolution, its’ constitution rejected checks and balances. They established a single legislative body elected by popular vote, which was given to any male over the age of twenty-one. There were no property qualifications for holding office and there was no governor. The purpose of this system was to create a simple form of government for the people to appeal to and work with. This kind of a system was favored heavily by revolutionaries because it spread political power broadly across the body politic.

In contrast, states like Maryland and New York created conventional representative democracies, which included a separation of powers, an upper body of the legislature, and a strong executive branch with the power to veto laws. They also instituted strict property requirements for voting and capital requirements for holding office. This system of government represented the vision of many of our Founding Fathers and at the time it was loathed by commoners because it was seen as a system that served the elite political class. In their minds, it insulated the people from the very forces of power that made policies impacting their lives. It was the anthesis of all of the values they fought for in the Revolutionary War.

These differences are important to understanding Shays’s Rebellion because in 1780, Massachusetts mirrored their constitution to a representative democracy favored by so many national leaders. It created a powerful governor with the right to veto and the privilege to appoint many public offices. It created two chambers of the legislature that weighted heavily in favor of the merchant class in the eastern part of the state. Finally, the state’s constitution raised property and capital requirements for voting and holding office. These changes were not welcome in many of the western towns that became the heart of Shays’s Rebellion a few years later. To them, the new constitution created a power structure that pandered to the Boston elite. Over the course of the decade, western counties would grew progressively frustrated as a distant and unresponsive legislature siphoned power from ordinary people and transferred it to the wealthy.

On the federal level, the Articles of Confederation created a weak national government that had little authoritative power in state affairs. Since the feds also couldn’t levy taxes to pay off national debt, they were forced to borrow money from abroad to stay afloat during the rough economic times immediately after the War. In order to pay off the resulting foreign debt, the government would send requisitions to the states, but there was no legal obligation on the states’ part to pay them off. Nevertheless, many in Massachusetts, especially the governing class, felt that it was necessary and beneficial to quickly make good on their requisitions. So much so that between 1780-1786, the Massachusetts legislature issued nine separate direct tax increases. These taxes were levied at the same time that the state was experiencing deflation and trade deficits due to recently closed markets in the British West Indies. The economic strain was particularly hurtful for western farmers, who were disproportionately low in cash, high in debt and taxed heavily. In 1783 alone, of the 199 towns that were delinquent on their taxes, 92 of them came from three western counties – Worcester, Hampshire, and Berkshire.

Adding to the dire situation was the fact that many of those experiencing rough economic times were veterans of the Revolutionary War. They had spent years away from their farms and families, and often had to hire help or take out loans to stay afloat. Since these soldiers were issued war bonds from the state, which were to be paid back in later years plus interest, they did not have the cash on hand during and after the War to pay back laborers and creditors, leaving them in crippling debt. Veterans were then forced to sell those bonds to speculators at a fraction of their value in order to make ends meet. So, instead of the state paying back those bonds to veterans, they were paying them to wealthy creditors that veterans were indebted to. As mentioned, the War also closed off markets in the lucrative British West Indies, which further depressed prices on crops and goods. As many farmers were falling deeper and deeper into debt, the markets provided little financial relief. What’s more, the Massachusetts state legislature passed strict measures to collect taxes and punish those that couldn’t pay of their debt. Those punishments included seizure of property and jail time. Even though county conventions were being organized and petitions were funneling in, primarily from western counties, the state legislature time and again rejected tax relief and debt relief measures, further fueling the notion that those in government were in the pocket of wealthy elites in Boston.

The seeds of rebellion that resulted from this began in 1782 from a Yale educated minster named Samuel Ely. Preaching in western counties throughout the state, Ely decried the corrupt state government and constitution. He advocated for direct confrontation with government officials in places like Hampshire County, which later became a hotbed for Shays’s Rebellion. Over the course of the year, Ely would be arrested, broken out of jail by local supporters, brought to Vermont, and arrested again, but by then the message had been sent; thousands of backcountry farmers were fed up with high taxes coupled with personal debt, they were fed up with an economic system that enriched a few wealthy creditors at the expense of many hard working veterans, and they were fed up with an unresponsive state government that functioned without accountability in a port city a hundred miles away.

After Samuel Ely’s short lived rebellion, some people appealed to the state government to listen to the concerns of the farmer class and create meaningful reforms. Joseph Hawley, for one, who was a Hampshire County resident and Massachusetts leader during the Revolution, wrote to his local representatives warning them that unrest in the region was severe and the threat of widespread rebellion was real. All of those warning calls fell on deaf ears with the election of David Bowdoin to Governor in 1785. Bowdoin doubled down on the policies that had created so much agitation in the years prior. He introduced a plan for the state to pay off its federal requisition and its interest on state debt simultaneously, he issued the largest direct tax of the decade, he enacted more stringent protocols for the collection of taxes, and he enforced harsher punishments for delinquency. Western counties became furious. County conventions were organized in Bristol, Middlesex, Worcester, Hampshire, and Berkshire counties where local representatives and community leaders demanded reforms that could provide some relief to those struggling to pay their taxes and bogged down by personal debt. Among their demands was a printing of more paper currency to generate the economy, a suspension of tax collections, and a halting of civil court cases that tried and punished individual debtors. A smaller faction of the convention goers called for more extreme reforms, like the abolishment of the state senate and a decrease in government salaries.

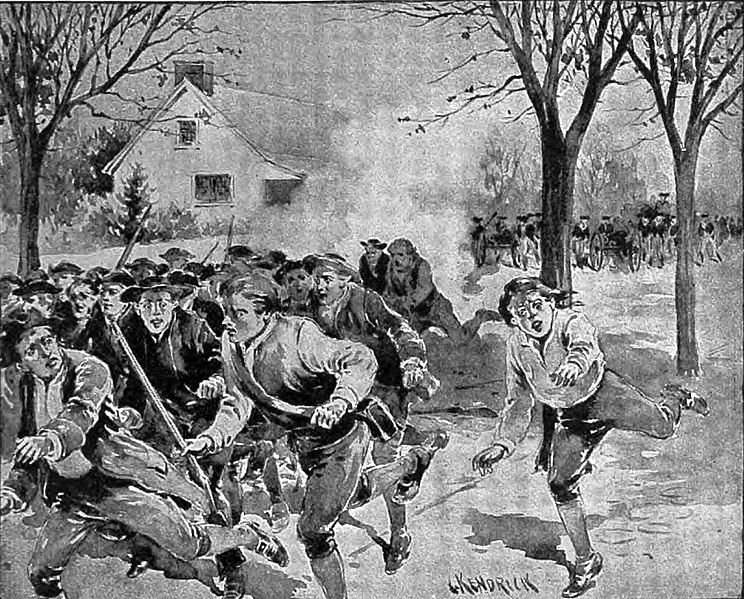

Instead of addressing these grievances, Governor Bowdoin and the state legislature adjourned the session in July of 1786 and vowed not to meet again or pass any emergency measures until the opening of the next session, in January 1787. Having attempted to work within the system, many in the western counties were at a loss. They had organized locally, created a comprehensive list of solutions, and appealed to their representatives, but they didn’t get so much as a consideration in response. For many, the only meaningful way to confront state leaders was with force, and that is exactly what they did starting in August of 1786, when up to fifteen hundred regulators, marching in regiments and brandishing weapons, seized the county court in the town of Northampton to stop civil cases to be heard. For the regulators, no government business should continue until their grievances had been addressed. The three judges of the court had no choice but to adjourn their session without hearing any cases. With that, Shays’s Rebellion had commenced. Throughout the fall, county courts closed in the face of armed regulators in Great Barrington, Springfield, Worcester, Concord, and Taunton.

The failed attempt by Daniel Shays’s regiment to seize the Springfield Arsenal ultimately doomed Shays’s Rebellion…

Shays’s Rebellion was mostly non-violent. Throughout the state, armies of regulators seized courthouses using the threat of violence as their weapon, but rarely exercised that threat. However, it wasn’t until Daniel Shays’s showdown in Springfield that the first shots were fired.

Although Shays had not taken a leadership position for most of the insurgency, by the end of 1786 and early into 1787, he led the largest regiment of regulators and was considered, based purely on rumor and speculation, to be the leader of the rebellion. However, historical records contradict the reports that had been widely circulated regarding his leadership position. Rufus Putnam, who had fought alongside Shays in the War, recorded a conversation he had with Shays right before the confrontation in Springfield. According to that conversation, “Shays denied being the leader of the regulators” and “all of the decisions to arm and organize themselves to close the courts were deliberative and reached by consensus, where he (Shays) was just one of many.” This is likely an accurate depiction of the Rebellion’s structure. While it had a passionate grassroots following, its leadership was decentralized. In fact, as one aide to the state militia suggested, if the regulators had a “respectable leader at their head” the rebellion could have caused enough trouble to “exhibit a scene that would alarm the continent.”

On January 25th, 1787, Shays led his regiment to a federal armory in Springfield. Anticipating their advance, local state militia commander William Shepherd and about 1,200 of his men occupied and guarded the armory days before Shays’s arrival. When Shays’s regulators encountered the militia at the armory, Shepherd ordered the first shots to be fired.

Not long after the first volley from the militia, the regulators dispersed despite the efforts from Shays and other regiment commanders to keep their troops in line. After the dust settled, three of Shays’s men had been killed and one of the state’s militia was injured. Daniel Shays and the rest of the regulators fled north and eventually settled in his hometown of Pelham, where local support allowed them to gain a defensive position.

After the short battle in Springfield, there were a few skirmishes in far west Berkshire County, but by the spring of 1787, it was clear that the rebellion had lost all momentum. Daniel Shays and many of the insurgents’ leaders sought shelter in neighboring Vermont and New York, where officials were not eager to aid the militia in Massachusetts. When it came down to issuing punishments for the thousands of regulators, state officials leaned on the side of reconciliation. Most regulators were given a pardon provided they paid a fee, surrendered their weapons, and took an oath of allegiance to the state of Massachusetts. While these terms for pardon were not offered to “leaders” of the rebellion like Daniel Shays, the militia was largely unable to track them down. Daniel Shays continued to live on the run in Vermont until the summer of 1788, when after sending a petition to the state of Massachusetts pledging loyalty and asking for forgiveness, he was given a pardon and allowed to return home free of punishment.

The showdown in Springfield was the climax of Shays’s Rebellion because it marked the most aggressive move by the regulators. It was speculated by newspapers and those close to the government that Shays’s attempt at the federal armory was a foreshadowing moment for the ultimate objective of the Rebellion – to seize hoards of weapons and ammunition that could be used to crush the forces of power in Boston. Whether or not that was Shays’s intention, the target being an armory instead of a county court was a clear escalation of the conflict and Shays’s role in that escalation further solidified his public perception as the Rebellion’s leader.

What’s striking about the growth of the regulators movement in the fall of 1786 is that, despite state leaders’ attempt to paint them as a group of renegades and outlaws, they had significant grassroots support in the countryside. The most revealing shortcoming of the political class in Boston was their ignorance to the roots of this grassroots support. Elites would pass off the regulators as a small band of poor and irresponsible debtors, but the truth is the regulation movement was proportionally distributed among all economic classes and included many prominent families. Some even tried to link the regulators with pro-British loyalists who were hell bent on destroying the new nation that freedom-loving patriots had fought for, but in reality, most Revolutionary veterans stayed neutral and ignored the call to arms for the state. In fact, up to thirty Revolutionary veterans of the Massachusetts line were active leaders in the uprising.

Above all, Shays’s Rebellion revealed a fundamental disagreement within the new nation about the meaning of their fight for independence. For small-town farmers, victory in the War was a triumph for individual liberty and hyper-localized democracy, but for many others, independence was a calling for national sovereignty and an opportunity for a unified nation to live up to ideals it set in the Declaration of Independence. This tension would finally be resolved in the Constitutional Convention, which was organized just a couple months after Shays’s Rebellion.

Shays’s Rebellion was a catalyst that led to the adoption of the U.S. Constitution…

Shays’s Rebellion was confined to the borders of Massachusetts, but its following spanned the entire nation because it confirmed the insecurities many national leaders had about the Articles of Confederation. Closely following from his home in Virginia, James Madison was very troubled by the rebellion, arguing “The insurrections in Massachusetts admonished all of the States of the danger to which they were exposed.”

For Madison, that danger was the creation of a national government that could not prevent the causes of, or respond to, an internal insurrection like Shays’s Rebellion. The Rebellion was in part caused by an economic recession, which was perpetuated because the Articles forbade the national government from regulating trade and currency. When the regulators started to organize into armed forces, the Articles prevented the national government from coordinating with other states to raise a national militia that otherwise should be able to swiftly respond to a force of Shays’s stature. Men like Madison watched from the sidelines as Shays’s Rebellion steered Massachusetts in the direction of lawlessness and anarchy. For that, they made the call for a new constitution that could address these shortcomings.

To be sure, the effort to change the Articles of Confederation had been taken up almost since its adoption in 1781. Headed by Alexander Hamilton and the Federalists, conventions had been called for in 1785 and 1786, but in both cases, the enthusiasm throughout the 13 states for a new constitution was tepid at best. However, when a new constitutional convention commenced in May of 1787, shortly after Shays’s Rebellion, the energy was much different. Leonard Richards, a professor from the University of Massachusetts, explains how Shays’s Rebellion “gave the nationalists the edge they needed. It provided the spark on which to advance the nationalist cause and play on the fears of others.” As Shays’s Rebellion was raging on, the federalist saw a silver lining: it provided fodder to their movement. Some, like General John Brooks, welcomed the chaos the regulators were causing, saying that “should the insurgents begin to plunder, I think it will have a good effect” on the call for a stronger national government.

It was clear in the words of federalists and federalists newspapers that those in favor of a stronger national government were completely infatuated with Daniel Shays. For the political class, Shays represented everything that was wrong with popular democracy. He was poor, classless, self-interested, and chaotic. He acted as the perfect scapegoat during the Constitutional Convention. Shays also put Anti-Federalists in an uncomfortable position, having to condemn everything that he stood for while also defending the system that allowed the rebellion to intensify. As one anti-federalist wrote in the Independent Gazetteer, the Constitution had been written “through the medium of a Shays.” All the federalists had to do was conjure up images of internal chaos to push the middle ground to favor the Constitution.

Perhaps most important for the federalists was the character contrast they could claim when George Washington re-entered public life to preside over the Constitutional Convention. For months during the rebellion, folks like James Madison and Secretary of War Henry Knox had been keeping Washington up to date on the situation in Massachusetts. Knox sent an alarming letter to Washington explaining that the insurgents “see the weakness of the government” and are exploiting that weakness to fight for “the common property of all.” Knox knew that these words played into the biases of Washington, who had amassed tens of thousands of acres through land speculation. He no doubt had experience with backcountry folk like Shays, who he described “as ignorant a set of people as the Indians.” In responding to the call to head the Virginia Delegation at the Convention, Washington perceived this moment as the ultimate opportunity “to rescue the political machine from this impending storm.” As the most revered figure in the country, Washington’s presence at the Convention in support of the Constitution turned the tide in favor of the Federalists. Conveying the significance of Washington’s participation, historians Rock Brynner and Leonard Richard put it best:

“his (Washington) participation in the formation of the new constitution provided the most effective propaganda the nationalists could engage to accomplish their objective”

– Rock Brynner“With Washington heading the Virginia delegation, with Washington accepting the post as presiding officer of the convention, the fifty-five men who met in Philadelphia that summer had to be taken seriously…He was their “trump card.”

– Leonard L. Richards

Simply put, Washington was the most important figure in the convention that wrote the Constitution, and his participation in that convention was directly influenced by Daniel Shays.

The framework of the Constitution was a response to the anxieties of the Federalists during Shays’s Rebellion. For them, the Rebellion was a concerning trend of civil disobedience that could plague any of the other 12 states because the nation functioned under a system that gave too much power to the “tyranny of the majority.” So, they created a system of checks and balances within the government to prevent radical shifts in society determined solely by popular will. Specifically, they created an Executive that was determined by an electoral college instead of the popular vote, an upper house of the Legislative branch that was elected by state legislatures and given 6-year terms so as not to subject every representative to frequent electoral shifts, and a judicial branch with life-time terms and the power to block unconstitutional actions by the other two branches. Importantly, the new Constitution gave the national government the power to organize a militia to “suppress Insurrection.” All of these elements were essential to creating a complex, conservative government that could stifle the growth of another Shays’s Rebellion.

Taking into effect the rhetoric about Daniel Shays from Federalists leading up to the Constitutional Convention, George Washington’s acute awareness of the Rebellion prior to deciding to preside over the Convention, and the elements of the Constitution that seemingly connected directly to the events of the Rebellion, Daniel Shays remains a historical oddity. A figure who is broadly unrecognized today, Shays was quite possibly the most important figure in developing and enacting our nation’s most important document.

Conclusion…

Shays’s Rebellion and the decade after the Revolutionary Way is crucial to understanding timeless themes of American politics: states rights vs. federal authority, the appeal of populism in the face of the status quo, and the perceived tyranny of political elites and the establishment. These are all issues that have persisted throughout the nation’s history, and have certainly intensified over the last few years with the election of Donald Trump and growing disillusionment of national institutions like the U.S. Congress and the mainstream media. Maybe if this story were more widely examined, our leaders would better understand the political phenomena that we see today.

A closer examination of Shays’s Rebellion also reveals so much about the vision of our Founding Fathers. Abraham Lincoln articulated that vision in the Gettysburg Address, when he called on his fellow countrymen to unite in defending a nation “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” However, if you take a close look at the ideas of Founders like Hamilton, Madison, and Washington, you would find that what was really intended was a nation for the people, and by the few. Hamilton went as far to say that “communities divide themselves into the few and the many” and it was important to ensure that the few had “a distinct permanent share in the government.” In 51 of The Federalist, James Madison wrote:

“In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty is this: you must first enable the government to control the governed, and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

I bet most Americans today, especially those in conservative circles, would be surprised to learn that some of our Founding Fathers warned of the “excesses of democracy” and championed government control over the people. Nevertheless, these are important ideas to recognize because they show that while our Founders valued individual liberty, they felt that liberty was best protected with a strong republic, barriers to direct democracy, and a meritocratic society.

For all of its undeniable merits, the Constitution was still a document written by a select few with their own biases, flaws, and personal ambitions. That is not to say the signers of the Constitution were primarily motivated by self-interest. Above all, there were driven by a commitment to justice and the common good. Regardless, the principles laid out in the Constitution caused a profound political debate, one that had its share of dissenters. In fact, many prominent historical figures, most notably Thomas Jefferson, were uneasy about the adoption of such a document. Since then, however, the Constitution has stood the test of time and today is the oldest living governing document in the world.

Resources

Condon, Sean. Shays’s Rebellion : Authority and Distress in Post-Revolutionary America. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015.

Richard, Leonard. Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

Gillon, Steven M. 10 Days That Unexpectedly Changed America. New York, Three Rivers Press, 2006.

Klarman, Michael. “The Framers’ Coup: The Making of the United States Constitution.” American Heritage, vol. 62, no. 4, 2016, http://www.americanheritage.com/framers-coup-making-united-states-constitution.

Incredible. Reminds us of how fragile the union was at the start.

LikeLike