I was first introduced to the American women’s suffrage movement during my junior year of high school. Towards the end of the school year, our U.S. history class was entering the 20th century in America and in between lessons on the Great War and the Great Depression, we spent a few classes discussing the struggles that “suffragists” endured to give women the right to vote in our country. Included in that lesson was a showing of clips of the movie, Iron Jawed Angels. Personally, I think the film did a pretty horrendous job of authentically portraying the nature of the 5 or so years leading up to the Women’s Suffrage Amendment. I must admit though that one sequence in particular did stick with me as a naive 16 year old: the prison scenes. These scenes depicted the brutal conditions suffragists experienced while being held in prison on trumped up charges. The re-enactments of prisoners being beaten and forced fed were jarring. It was part of the reason my curiosity for this period persisted for years after high school. Thanks to amazing educators, peers, and authors, I’ve learned a lot about a movement that many feel is largely overlooked in our public curriculums.

The truth is, the American women’s suffrage movement was a long, strenuous battle. The women that led this century-long fight were gritty, brash, creative, and courageous. They had to be! Fighting against almost every established power structure during their time, they experienced crushing failures and setbacks. They were constantly dismissed, ridiculed, and ignored. But their relentless pursuit for equality resulted in groundbreaking reforms that transformed American social life.

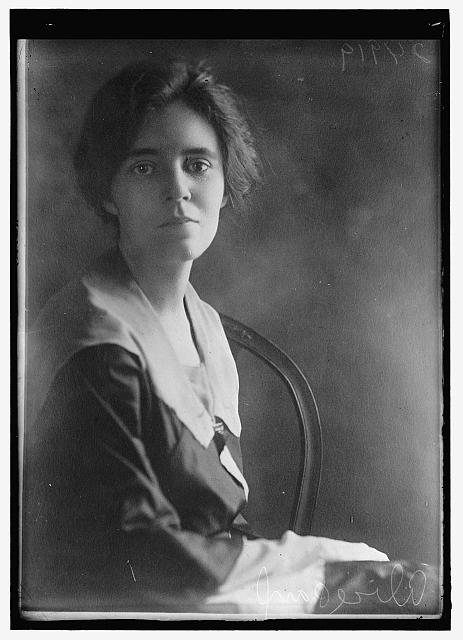

I’ve chosen to focus on Alice Paul as the catalyst for this story because of the dynamic change that occurred largely due to her leadership in the women’s suffrage movement. She emerged in the suffrage movement just after the period referred to as the “the doldrums.” For almost two decades at the turn of the 20th century, the suffrage movement seemed like a slow moving ship with no destination in sight. Little progress had been made at the state level and public enthusiasm for women’s rights was low. Alice Paul came in and completely revitalized the movement. Making the suffrage amendment front and center in the public debate, Paul and her fellow suffragists accomplished in a matter of a decade what so many in the movement had been seeking for almost a hundred years. Still, the events and leaders building up those one hundred years are instrumental to this story.

The American Women’s Suffrage Movement was a century-long fight that endured periods of stagnation, division, incremental progress, and rapid change…

The Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 is traditionally considered the start of the women’s suffrage movement, but to truly understand the forces and desires that led to that moment, it is important to consider broader women’s rights movements in the United States prior to 1848. In the first half of the 19th century, women’s rights leaders fought for progress in the areas of education, abolitionism, and labor.

During this time, conventional wisdom had it that women were inferior to men physically and mentally. A women’s brain did not have the capacity to comprehend science, math, law, philosophy, etc. Even the earliest advocates for greater opportunity in women’s education were drawn to the concept that with more knowledge, women could become better mothers and housewives.

Pioneers like Emma Willard and Frances Wright were among the first activists to advance educational opportunities for women. As a tireless advocate in the New York state legislature, Emma Willard was able to secure funds to found the first women’s seminary in 1821, which offered courses in science and physiology. Later in the 1820’s, Frances Wrights’ introduced the “radical” idea that women deserved an equal education to that of a man’s. As a public orator to this idea, she received notoriety, but also resonated with working class men and women. A decade later, Mary Lyon became perhaps the most important figure in broadening education for women. She founded Mount Holyoke in 1837 with such a strong financial backing that she was able to support a rigorous and comprehensive curriculum, including grammar, geography, history, physiology, science, philosophy, and math. The success of Mount Holyoke, still open to this day, represented the realization of the vision that women like Willard and Wright put forth a decade before: that women were capable of succeeding in the most sophisticated academic disciplines, that their education was a benefit to society, and that the publics’ support for their schools was a meaningful investment. Mary Lyon’s progress paved the way for women universities throughout the country, like Vassar, Smith and Wellesley, and Bryn Mawr. What’s more, many students at these early seminaries would later become leaders at the Seneca Falls Convention.

As these groundbreaking reforms in women’s education were taking place, the abolitionist movement was sweeping the country. Historian Eleanor Flexner outlined the convergence of women’s rights and abolitionism in Century of Struggle, writing:

“It is in the abolition movement that women first learned to organize, to hold public meetings, to conduct petition campaigns. As abolitionists they first won the right to speak in public, and began to evolve a philosophy of their place in society and of their basic rights.”

The abolitionist movement provided women a platform to make their voices heard and eventually extend their advocacy for that of women’s rights. The earliest examples of this transition are the Grimke sisters, Sarah and Angelina. Born in South Carolina to a slaveholding family, they moved up north after childhood and allied with the American Anti-Slavery Society. Providing firsthand accounts of the evils of slavery, their speeches across the northeast marked the first time women spoke in public to an audience of mixed gender. Angelina later became the first woman to address a legislative body when she defended an anti-slavery petition in front of the Massachusetts state legislature in 1838. As their popularity spread, their opposition grew. Church leaders decried their “unnatural” presence on the public stage and even leaders of the abolitionist movement feared that their inclusion would drown out the overarching message of abolitionism. However, their refusal to stay silent on the issue of abolition extended to their fight for women’s rights as they constantly defended their right and value to contribute to political life. The Grimke sisters were an inspiration for women’s rights leaders generations after their time because they represented the plight of countless women, whose advocacy on any issue had to begin with a defense of their right to advocate on that issue in the first place. Who could embody that struggle more than Sojourner Truth, who’s famous “Ain’t I a Woman” speech exposed the ignorance of so many antifeminists during this time.

The first half of the 19th Century saw a huge upsurge of women in the workplace, particularly in the textile industry. With the invention of the spinning jenny and the power loom, large textile manufacturing plants were popping up all over the northeast. Since advanced training programs were not available to women at this time, these low-skill factory jobs were their only option and since they were seen as inferior, you can bet their wage was far lower for similar work to that of a man’s. This cycle provided another arena for women to speak out. Although low pay and social status greatly hindered the strength of women organized labor, tremendous progress was made in this field in the 1830’s and 1840’s. The Lowell Female Labor Reform Association, led by Sarah Bagley, is considered the first established women’s labor union. Fighting for a ten-hour workday, better conditions, and more pay, their unification brought the issue of women labor rights to the forefront. Although they did not win reform for many of their grievances, their advocacy brought about the first investigation into labor conditions in the state of Massachusetts.

I don’t believe you can have a complete conversation about the women’s suffrage movement without acknowledging the efforts made in education, abolition, and labor about 100 years before the suffrage amendment was passed. The sacrifices, struggles, and victories made by feminists during this period paved the way for the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 and the eventual passage of the women’s suffrage amendment in 1920.

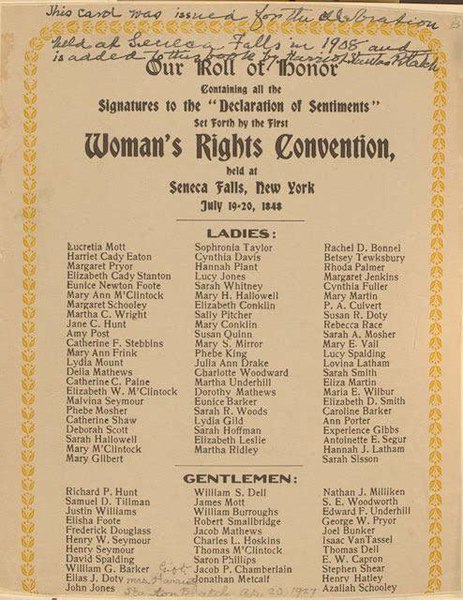

The very idea of the Seneca Falls Convention originated with a young activist by the name of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Growing restless from her life as a housewife, Stanton reflected on the struggles women faced in their own personal development as a result of their place in society. Together with Lucretia Mott, they planned the Convention to be held on July 19 and 20, 1848 at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York. It was an informal meeting with a broad focus: to discuss the social, civil, and religious rights of women. The most important document to come out of the convention was the Declaration of Sentiments. Modeled after the Declaration of Independence, the document outlined the rights of women in the areas of marriage, divorce, property, education, public participation, and more. Following the signing of the Declaration, the convention considered 12 resolutions related to women’s rights. Ironically, the only resolution not to pass unanimously, though it did pass by majority, was the right to vote.

Therein lies the primary significance of the Seneca Falls Convention to the women’s suffrage movement. For the first time, an organized group discussed and agreed upon a woman’s right to vote in the United States. While there were many other issues that were addressed and would progress over the decades within the broader women’s rights movement, the issue of enfranchisement became the beacon that feminists leaders in this country followed, up until its victory in 1920.

Following the Civil War, the abolitionist movement and the women’s rights movement officially unified in 1866 under the American Equal Right Association (AERA). With the mission to further the rights of women and African-Americans, AERA became the first national organization advocating for women’s rights. This unification did not last long, however. That same year, Congress introduced the 14th Amendment, extending citizenship to former slaves that were freed in the Civil War. A faction of the AERA, including feminists icons Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, took issue with Section 2 of amendment, which addressed penalties to states that violated “any male inhabitant” of their right to vote. The explicit exclusion of women in a provision of the Constitution pertaining to the right to vote was a disqualifying factor for many in the AERA. This created a schism, with the Anthony-Stanton faction of the AERA opposing the 14th Amendment and the rest of the AERA supporting the amendment. Eventually, the 14th Amendment was ratified, and not long after it the 15th Amendment, which prohibited any state from denying one the right vote “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude” (notably excluding “sex”). By this point, the divide between the rival factions in the AERA was to wide to mend and the Anthony-Stanton faction split to form the National Women’s Suffrage Association (NWSA) in May, 1869. Shortly after, Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe founded the American Women’s Suffrage Association (AWSA).

From 1870 – 1890, the divide between the NWSA and the AWSA was apparent both in their respective culture and mission. The NWSA was considered “aggressive and unorthodox.” They challenged authorities, societal norms, and established institutions. Led by Susan B. Anthony, their tactics were meant to be disruptive, as they were in 1872 when several members including Anthony were arrested for illegally voting in the presidential election. The NWSA saw their fight as a broad movement for women’s rights, so they included labor, religion, marriage, divorce, legal status etc. in their activism. On the other hand, The AWSA was conventional and conservative. They focused solely on the vote and they felt that meddling with other social issues would only agitate potential supporters that were needed to sway influential members of government and society. During this time of division, the only major victory for suffrage came in 1878, when the Suffrage Amendment was finally proposed in Congress. Though the amendment did not advance, its language remained the same throughout the movement, and became the official outline of its eventual passage in 1920.

Towards the end of the 19th century, it was clear that the mood of the women’s suffrage movement was siding more with the AWSA, so in 1890, the AWSA and NWSA unified to form the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Adopting the conservative mood of the AWSA, the newly formed NAWSA vowed to focus squarely on the suffrage issue, and to accomplish suffrage incrementally in the form of state referendums. However, success on this front was few and far between. From 1870-1910, NAWSA launched 480 campaigns in states across the country. In that time only two states, Colorado and Idaho, adopted women’s suffrage. The movement not only failed tactically, but also spiritually. 19th century feminist leaders like Anthony, Stanton, and Stone all passed away during this time, leaving a vacuum in the movements leadership. Eleanor Flexner sums up the lowly years in the early 20th century in Century of Struggle:

“In point of fact, interest in the Federal woman-suffrage amendment was at an alltime low. The annual hearings on the bill before the Senate and House Committees had become routine, since nothing was expected to come from them. Women suffrage had not been debated on the floor of the Senate since 1887, and had never reached the floor of the House; the suffrage bill had not received a favorable report in either house since 1893, and no report at all since 1896.”

The American women’s suffrage movement was in turmoil. Their tactics were ineffective, their leadership was transitioning, and their impact was minimal. The movement needed someone to come in to re-energize the base and reignite the flames of feminism. In 1913, that person was Alice Paul.

Alice Paul’s unconventional and confrontational strategies catapulted the Women’s Suffrage Movement to the forefront of American politics…

Alice Paul grew up in New Jersey to a Quaker family. As members of the “Hicksite” sect of the religion, her family was “more inclined to educate women then their orthodox adversaries,” as Mary Walton writes in A Woman’s Crusade. With encouragement from her community, Paul excelled in school and eventually attended Swarthmore College, a Quaker university whose intended mission was to “prove what has yet been fully proven…that it is feasible and desirable to give to woman equal educational facilities with man.” Paul continued her studies in social work in England through a grant given to her by her Quaker community. In these formative years in England, Paul became active with the Women’s Social and Political Union, a radical feminist movement that practiced aggressive tactics, including pickets, hunger strikes, and vandalism to fight for suffrage. It was also in England that Paul met a fellow American feminist activist, Lucy Burns. They would return to the U.S. in 1912 and become partners in crime when they linked with NAWSA and the American women’s suffrage movement.

Paul and Burns made their presence known early on with NAWSA. Paul was appointed chairman of the Congressional Committee, whose focus was in Congressional outreach in Washington, D.C. Embodying their penchant for disruption, Paul and Burns first opportunity came in organizing a march of 5,000 “suffragists” in Washington, D.C. the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration in 1913. Nothing will get more attention than disrupting the plans and expectations of the incoming President of the United States, and that’s exactly what they did. As Wilson arrived to Washington to greet the crowds awaiting his inauguration the next day, he found the streets were relatively empty. He was informed that all of the attention was directed to Pennsylvania Avenue, where thousands of women were marching for the suffrage amendment.

The crowds that gathered along Pennsylvania Avenue grew from curious to angry. The site of so many women publicly protesting was an outrageous scene that incited violence in many. One newspaper described the parade as chaotic: “The women had to fight their way from the start and took more than one hour in making the first ten blocks. Many of the women were in tears under the jibes and insults of those who lined the route.” Although the group was promised a police permit, the officers under leadership of the D.C. Commissioner refused to protect marchers that were under attack. The underlying success of the march came from the public reaction following its completion. Newspaper reports of the vitriol the women faced and the composure they maintained instilled a sense of sympathy for their cause. Paul and Burns’ coming out party via the parade was hugely successful. Not only did they garner a level of attention that the suffrage movement hadn’t seen in years, they also favorably influenced public opinion.

However, leaders of the NAWSA grew weary of Alice Paul. While they recognized the increased attention the suffrage issue was receiving, they were concerned that Paul’s uncontrollable habits would hurt their cause in the long-run. Meanwhile, Paul used her momentum to create the Congressional Union (CU), an affiliate to NAWSA that focused solely on passing the Federal suffrage amendment. Alice Paul’s rapid emergence in the NAWSA was eventually met with pushback at their national meeting in 1913. Paul clashed with the NAWSA about the long-term strategy for the federal amendment. Taking matters even further, Paul was accused of misappropriating NAWSA funds in her pursuits with the CU and the executive board limited the CU’s power to dictate NAWSA policies. Once again, the movement was divided when Alice Paul and the rest of the CU split from the NAWSA in 1914.

One of the chief tactical disagreements between Alice Paul and the leaders of the NAWSA concerned the movement’s relationship with the political establishment. Alice Paul argued that they should target the party in power regardless of their individual members’ position on women’s suffrage. The NAWSA on the other hand had been working for years to gain respect and social status among influential circle in national and state politics, so hence disagreed with any efforts to stifle the relationships they had built with their supporters. When the CU and the NAWSA split, Paul had the freedom to execute her strategy of confrontation, accountability, and reform. The CU’s message to Democrats was simple: use your political power to pass women’s suffrage, or we will apply electoral pressure and threaten your majority. This strategy came to a head in 1916, when they officially campaigned against Woodrow Wilson in the Presidential Election.

Meanwhile, the NAWSA continued to support grassroots movements for state referendums and claimed victories in several states. However, these victories were predominantly in smaller western states, like Arizona, Kansas, Montana, Oregon, and Nevada. The shortcomings of their strategy was felt in more influential states like New York, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, which rejected suffrage amendments in 1915. That same year, there was a leadership shakeup at the NAWSA. Anna Howard Shaw, who had served as President since 1904, stepped down and handed over the reins to Carrie Chapman Catt. This change in leadership was a significant development for the NAWSA and the suffrage movement as a whole. While Shaw had been a fearless leader for the movement for decades, there was growing discontent with her leadership. Catt initiated broad organizational improvements to the NAWSA that included congressional lobbying for the federal amendment.

Alice Paul and the suffragists decision to picket the White House was a galvanizing moment in the U.S. and led to eventual passage of the 19th Amendment…

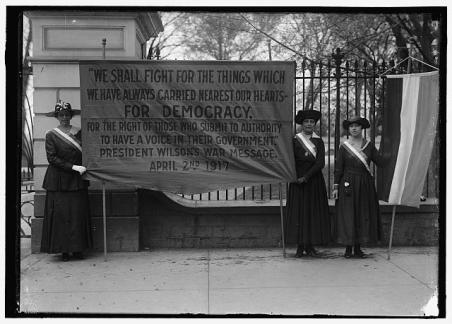

Alice Paul and the CU, now named the National Woman’s Party (NWP) amplified their confrontational tactics after their failed effort to try to unseat Woodrow Wilson in the 1916 Presidential Election. Taking from what they learned years ago in England, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns organized the nation’s first ever pickets outside the White House in January, 1917. At first, these pickets gained little attention – even Woodrow Wilson would politely wave or tip his cap when he walked by picketers each morning. However, that started to change in April, when the U.S. entered World War I. The general public, especially servicemen, did not take kindly to women publicly criticizing the administration at a time when national propaganda was promoting patriotism.

The “silent sentinels” as the picketers came to be known, felt the exact opposite. The U.S. involvement in World War I was the perfect opportunity to reveal the utter hypocrisy of the Wilson administration. So, at the same time that public opinion of their protests started to sour, the picketers’ rhetoric intensified. They referred to the President as “Kaiser Wilson”, they invoked biblical passages, and they mocked Wilson’s contradictory statements. One of the Silent Sentinels, Doris Stevens, chronicled the mob mentality that developed from these protests in Jailed for Freedom. At the height of the tension, in August 1917, Stevens describes the crowds violence towards the picketers:

Alice Paul was knocked down three times by a sailor in uniform and dragged the width of the White House sidewalk in his frenzied attempt to tear off her suffrage sash.

Miss Katharine Morey of Boston was also knocked to the pavement by a sailor, who took her flag then darted off into the crowd. Miss Elizabeth Stuyvesant was struck by a solider in uniform and her blouse torn from her body. Miss Maud Jamison of Virginia was knocked down and dragged along the sidewalk. Miss Beulah Amidon of North Dakota was knocked down by a sailor.

The administration was starting to grow restless of the picketers, but they did not know how to quell their protests. Clearly, the picketers could no longer be ignored with a tip of the cap from President Wilson. They were making their presence known and becoming the subject of unrest in the streets. Starting in June 1917, President Wilson and D.C. Chief of Police Major Pullman ordered the arrests of picketers with the hopes of suppressing their efforts. Knowing they could not charge the women for picketing, which was protected under the law in the Clayton Act of 1914, the D.C. police jailed the women for an arbitrary charge of “obstructing traffic.”

To the administration’s surprise, the arrests did not dampen the spirit of the NWP, who continued to picket the White House while accepting that they would be arrested for “obstructing traffic.” Meanwhile, those that were arrested were then sentenced to 60 days imprisonment in Occoquan Workhouse, in Virginia. What is often lost in this story, and which influenced public outcry against their arrests and against the conditions of their imprisonment, was the fact that many of the suffragists were high members of society. In fact, several of the women imprisoned and subject to brutal treatment in jail were the wives or family members of journalists, lawyers, politicians, etc. In one instance, Senator J. Hamilton Lewis of Illinois was called to the prison following a complaint from one of his constituents, Lucy Ewing, a suffragist prisoner who also happened to be the niece of former Vice President Adlai Stevenson. Upon visiting with Lucy and witnessing the conditions at the prison, Senator Williams remarked, “In all my years of criminal practice, I have never seen prisoners so badly treated, either before or after convictions.” Unfortunately, that was an accurate portrayal of the time spent at Occoquan Workhouse for the suffragists. As chronicled by Doris Stevens, these women were given a single bar of soap to share collectively for washing, blankets that had not been cleaned in months, food infested with worms, and beatings by the prison guards. Virginia Bovee was a Matron at the prison during this time. She described the beatings to the NWP after her time at the prison in an effort to bring to light the treatment of prisoners at the workhouse: “I know of one girl beaten until the blood had to be scrubbed from her clothing and from the floor of the ‘booby house.'”

Lucy Burn’s courage and toughness during the days at the Occoquan Workhouse were heroic. As the vocal leader of the suffrage movement at the time, she led the women in the workhouse by demanding that they be treated as political prisoners. Having that request denied time after time, Burns inspired the women to organize hunger strikes in the prison, a tactic she had learned when she served in prison with Alice Paul in England while fighting for women’s suffrage abroad. This show of defiance from the prisoners led to unspeakable offenses by Superintendent Whittaker and other prison guards. The most extreme of these offenses came on what is today considered “The Night of Terror” November 14, 1917. The accounts from dozens of prisoners that were brutalized during The Night of Terror illustrate a horrific episode of state violence against domestic political prisoners in our country. Keep in mind when reading these accounts that the victims of this abuse were imprisoned for “obstructing traffic.” They were peacefully picketing outside the White House so they could gain the right to vote in their own country.

Lucy Burns managed to log a day-by-day account of her time in prison. Her log from The Night of Terror and days after reads in part:

“Dr. Gannon told me then that I must be fed. Was stretched on bed, two doctors, matron, four colored prisoners present, Whittaker in hall. I was held down by five people at legs, arms, and head. I refused to open mouth. Gannon pushed tube up left nostril. I turned and twisted my head all I could, but he managed to push it up. It hurts nose and throat very much and makes nose bleed freely. Tube drawn out covered with blood. Operation leaves one very sick. Food dumped directly into stomach feels like a ball of lead. Left nostril, throat, and muscles of neck very sore all night.”

Another suffragist, Dora Lewis, described her ordeal on The Night of Terror:

“I was seized and laid on my back, where five people held me, a young colored woman leaping upon my knees, which seemed to break under the weight. Dr. Gannon then forced the tube through my lips and down my throat, I gasping and suffocating with the agony of it. I didn’t know where to breathe from and everything turned black when the fluid began pouring in. I was moaning and making the most awful sounds quite against my will, for I did not wish to disturb my friends in the next room.”

Mary Nolan, a 73 year-old suffragist from Florida detailed the abuse her and a few other prisoners suffered:

“I saw Dorothy Day brought in. She is a frail girl. The two men handling her were twisting her arms above her head. Then suddenly they lifted her up and banged her down over the arm of an iron bench – twice. As they ran past me, she was lying there with her arms out…”

Then her time in the prison cell:

“We had only lain there a few minutes, trying to get our breath, when Mrs. Lewis, doubled over and handled like a sack of something, was literally thrown in. Her head struck the iron bed. We thought she was dead. She didn’t move. We were crying over her as we lifted her to the pad on the bed…”

Remarkably, this physical and psychological abuse did not deter the suffragists. The dozens of prisoners continued their hunger strikes day after day for almost two weeks after the Night of Terror. On November 27 and 28, 1917, the suffragists were released from prison and their sentences were invalidated a few months later.

The impact of the picketers and their imprisonment is immense. For one, the picketers drew a level of publicity that launched the suffrage issue into the mainstream political debate. Especially in cases where these protesters were subject to violence, the coverage led to more attention to the issue of women’s suffrage and sympathy for those that were suffering for its enactment. This also led to actionable measures within Congress that moved the suffrage issue forward: the Senate Committee on Suffrage issued a favorable report on the amendment on September 15, 1917 and the House Committee on Women’s Suffrage was appointed on September 24th, 1917. A week after the Silent Sentinels were released from jail, the House scheduled a vote on the amendment. The date that the suffrage amendment was passed in the House, January 10th, 1918, was exactly one year after the first picket of the White House. This was all part of Alice Paul’s strategy – to confront the American public about their injustices and hold elected leaders accountable for their inaction.

There is still something to be said for the almost polar opposite strategy of Carrie Chapman Catt and the NAWSA. Choosing a much more conciliatory approach, the NAWSA publicly supported the war and contributed to the war effort by joining a committee for the Council of National Defense. The NAWSA’s grassroots on the state side was also gaining traction. They finally passed a suffrage amendment in New York in 1917, the country’s largest state at the time. Perhaps the NAWSA’s close relationship with Woodrow Wilson in the time of war and the growing list of states to pass suffrage influenced him enough to finally support the suffrage amendment right before its vote in the House of Representatives in 1918.

On January 10, 1918, the House passed the suffrage amendment, 274 to 136, exactly the two-thirds majority needed to pass a constitutional amendment. Given the slow nature of our government, especially for amendments to the constitution, full passage of the 19th Amendment was not ratified until over two and a half years after its initial passage in the House. In the Senate, opponents tried for months to delay and defeat the amendment, though it was finally passed on June 4, 1919.

As if this fight isn’t dramatic enough, the final step in passing the 19th Amendment, ratification from 3/4 of state legislatures, reads like a movie script. Suffragists needed to secure 36 of the 48 states to ratify the amendment. Knowing that many southern states would refuse to vote on ratification, there was very little wiggle room. By August of 1920, 35 of those 36 states ratified the amendment. Tennessee agreed to vote on ratification that month and was considered to be suffragists’ last hope to gain ratification before the 1920 Presidential Election. For almost the entire summer, both pro- and anti- suffragists lobbied the state house aggressively. When the deciding vote came on August 18, 1920, a young man by the name of Harry T. Burn became the unsung hero. Burn became the youngest member of the Tennessee State Legislature when he was elected in 1918 at the age of 22. Now facing the pivotal vote of ratification of the women’s suffrage amendment, Burn originally signaled that he would be voting against ratification. As the roll call was wrapping up, the vote was tied 48-48. Burn had been stalling, something was conflicting him. Little did the chamber know that Burn had received a letter from his mother the morning of the vote which read:

Dear Son:

…Hurrah and vote for Suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt. I noticed Chandlers’ speech, it was very bitter. I’ve been watching to see how you stood but have not seen anything yet … Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. ‘Thomas Catt’ with her “Rats.” Is she the one that put rat in ratification, Ha! No more from mama this time…

With lots of love, Mama.

When it came time for him to vote, Burn broke the tie, but to everyone’s surprise, he changed his vote and supported ratification, thereby securing the 3/4 majority needed to certify the 19th Amendment and enfranchise 26 million women. The next day, Burn defended his vote in a floor speech, saying in part: “I knew that a mother’s advice is always safest for a boy to follow and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification.”

Simply remarkable. An idea that originated in a chapel in upstate New York in 1848 – which was inspired by decades of social pioneering, which was undermined by the country’s most powerful institutions, which had evoked passion to the point of violence and division, and which had suddenly emerged in the mainstream of American politics – was finally made a reality by a single vote from one of the last states that could decide its fate.

Conclusion…

What’s fascinating to me about the final years of the women’s suffrage movement is that there were two rival organizations deploying conflicting strategies to arrive at the same goal. Alice Paul and the NWP were loud, disruptive, and functioning outside of the power apparatus they were appealing to. Carrie Chapman Catt and the NAWSA were deliberate, amicable, and striving to be insiders with the key figures deciding the movement’s fate. Which one was more effective in bringing about the desired change? I would side more with Alice Paul and the NWP.

There are clear links of the major milestones of the movement to the actions taken by Alice Paul and the NWP. For one, the year she split from the NAWSA to form the Congressional Union, the suffrage amendment was brought to the House floor for a vote for the very first time and brought to the Senate floor for a vote for the first time in the 20th century. As I mentioned above, exactly one year after the Alice Paul led pickets on the White House, the amendment was passed in the House. Alice Paul also introduced a robust lobbying effort, which sent teams of suffragists to meet with the President on multiple occasions. Carrie Chapman Catt later acknowledged the effectiveness of their lobbying when she took over the NAWSA in 1915. It was largely due to Paul’s operation that Catt choose to invest more in the NAWSA’s federal lobbying arm, which was then later credited for building the necessary relationship with President Wilson to secure his support for the amendment in 1918.

In that time, the NAWSA was working tirelessly and effectively in state referendums, federal lobbying, and wartime support. Without their contribution, congressional and presidential support likely would have dwindled. What’s more, their organized state operations became instrumental in securing ratifications from the 36 states.

So, there is no doubt that each of these organizations were important to the passage of the 19th amendment. But where Alice Paul was so successful, time and time again, was public relations. She drove public discourse and took the issue of women’s suffrage to a political relevancy in the United States that it had never seen before. That type of impact is invaluable in American politics.

Though it may not get the credit it deserves today, passage of the 19th Amendment is one of the most significant moments in 20th Century American history. Twenty six million women were added to the American electorate. With that, policies and politicians that dictated those policies shifted according to the new electorate. This led to laws that protected reproductive rights, invested more in education and social programs, improved economic opportunities for women, and expanded healthcare services. Their success in the public realm also encouraged more women to run for office at every level of government. At the time of the passage of the 19th Amendment, there was only one women in Congress, Jeannette Rankin of Montana. Today, there are 127 female members of Congress, on top of the women that have taken leadership positions in state and local politics. Above all, the women’s suffrage movement was a testament to the strength of American Democracy. A virtually powerless class of society was able to create historic change through civic action and political engagement. Their story has influenced social and cultural movements throughout the world.

Following passage of the 19th Amendment, Alice Paul went right back to work in fighting for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). The ERA seeks to codify into the Constitution that equal rights should never be discriminated against on the basis of sex. Alice Paul believed the true fight for equality would not be complete until passage of the ERA. Though the amendment passed both houses of Congress in 1972, it was not ratified by the necessary majority of states and has not been taken up in Congress since then. Alice Paul unfortunately passed away in 1977 at the age of 92 without completing her final political fight. Maybe the 100th year anniversary of the 19th Amendment will revitalize the Equal Rights Amendment in the same way its author, Alice Paul, did for the Suffrage Amendment so many years ago…

Resources

Flexner, Eleanor. Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States. 1959, 1975, 1996, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Walton, Mary. A Woman’s Crusade: Alice Paul and the Battle for the Ballot. 2010, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, New York.

Stevens, Doris. Jailed for Freedom. 1920, Boni & Liveright Publishers, New York, New York.

Williamson, Heidi. “Women’s Equality Day: Celebrating the 19th Amendment’s Impact on Reproductive Health and Rights.” Center for American Progress, 8 July 2014, http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/news/2013/08/26/72988/womens-equality-day-celebrating-the-19th-amendments-impact-on-reproductive-health-and-rights/.