The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand at the hand of Gavrilo Princip is commonly considered the spark that led to World War I. Within months of the assassination, a ripple effect of war declarations and troop mobilizations consumed Europe. For the next four years the major powers of the world would engage in a conflict that would take the lives of over 10 million people, lead to the collapse of four global empires, and forever change the world map. As Vladimir Dedijer wrote in The Road to Sarajevo: “No other political murder in modern history has had such momentous consequences.”

Isn’t it odd then that the main actor of such a monumental event is today largely unknown? Gavrilo Princip is remembered merely as that guy who killed Franz Ferdinand, but rarely do we think about what brought him to that moment. How was his upbringing? What were Princip’s plans and motivations? Did he foresee that this assassination would lead to a conflict that still defines our lives? Diving into Princip’s life and the impacts of the assassination reminds us that many of history’s most defining moments are sparked by the most unlikely of characters.

Gavrilo Princip was buried in the lower echelons of a hierarchical society…

If you traced Gavrilo Princip’s life from an early age, you wouldn’t think that he’d go on to commit the most “momentous political murder in modern history,” according to our friend Dedijer. Gavrilo was born to a poor peasant family in the western highlands of Bosnia, in the village of Oblajaj. He was known by many in the village as quiet, reserved, and lonesome. He’d rather spend his days with his favorite book than with his favorite friends. However, as Tim Butcher illustrates in The Trigger, one can reveal a more complete picture of Gavrilo with a relentless curiosity and a pair of restless legs.

In an excursion through Gavrilo’s upbringing, Butcher interviews Gavrilo’s descendants in Oblajaj. They describe Gavrilo as quiet and small, but also tough. Gavrilo “always fought for those who would not defend themselves.” Through careful examination, Butcher presents traces of the firebrand revolutionary Gavrilo became. He was known in the village by those that were close to him as a ferocious opponent of authority. There are stories of him fighting against bullies in the yard, teachers at school, Austrian policemen on the streets, and eventually Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo.

Those details aside, Gavrilo was an otherwise ordinary member of his society. He was in and out of schools for much of his adolescence. Due to his small and weak stature brought on by tuberculosis, he was often bullied and looked down upon by his peers. Even in the days leading to his radicalization with the Young Bosnians, he was excluded from primary roles in most of their plots. If it wasn’t for a fluke run-in with Ferdinand’s party outside of a cafe Gavrilo happened to be commiserating in on the day of the assassination, he would not have committed the fatal act. Maybe it was that massive chip on his shoulder from a life spent in second-class society that drove him to take matters into his own hands.

What strikes me most about the assassination and the carnage that it led to was that it was caused by a teenage delinquent with no power or influence in the life around him. Europe was in turmoil, there’s no doubt about that. Tensions were so high that any one of the major powers could have ignited the fire of World War I by as little as a snarky telegram to a rival. But it was a poor peasant from Bosnia with a terminal illness and a contempt for the establishment that did the deed. Reflecting the sentiments of so many that have explored this story, Butcher writes, “I too found it extraordinary that a boy with a childhood of such limited horizons could go on to precipitate events that would change the world.”

Princip’s single act – assassinating Franz Ferdinand – accelerated a global conflict the world had never seen before…

Even among political assassinations, the story of Franz Ferdinand’s assassination is an anomaly.

To fully understand the circumstances of the fatal meeting between Princip and Ferdinand, it’s important to recognize the historical background preceding the moment. The beginning of the 20th century was particularly dynamic for the Balkans. As the subjects of a power struggle between Austria-Hungary, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire, nationalistic fervor was high in Southeastern Europe. When Austria-Hungary officially annexed Bosnia in 1908, Serbia went on the offensive. With a shared sense of ethnic and geographic ties to the Bosnian people, Serbia demanded portions of the annexed territory. It was during this time that Gavrilo Princip started to evolve his radical political beliefs and ambitions. Leaving the countryside in his teenage years, he attended a number of boarding schools in Sarajevo and eventually moved to Belgrade where he received a Serbian nationalistic education and became involved with the Black Hand, a Serbian nationalist movement comprised of young adults.

During Princip’s radicalization, tensions between Austria-Hungary and Serbia intensified. However, with Germany backing Austria-Hungary and Russia backing Serbia, the threat of a large European conflict prevented either side from taking drastic actions. That all changed when Princip made his return to Sarajevo in 1914…

Parading down the main streets of Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, Franz Ferdinand had a full day planned with the troops and leaders of the Hapsburg’s recently annexed Bosnian people, starting with a welcoming procession leading up to City Hall. Princip and his co-conspirators lined the streets of Ferdinand’s motorcade anxiously waiting for their opportunity to take the Archduke down. The first attempt, a grenade thrown in the direction of Ferdinand’s car, missed the target and exploded under the car behind Ferdinand. This caused a frenzy, as Ferdinand’s party hurriedly drove off and the conspirators, including Princip, were left with nothing.

What happens next is simply unbelievable. Against the advice of those around him, Ferdinand decided to visit the hospital treating the officials that were injured in the explosion earlier in the day. In order to avoid further crowds, one of Ferdinand’s generals instructed the party to take an alternate route to the hospital, one that would go around the city center. This information was apparently not relayed to the driver, as he followed the other two cars to the hospital by turning onto Franz Josef Street. Gavrilo and his cronies happened to be at a cafe on the same street, sulking over their missed opportunity. Seeing Ferdinand’s ride stalled right in front of the cafe, Princip jumped out, pulled a handgun out of his jacket, and fired several shots into Ferdinand’s car, killing both the archduke and his wife, Sofia.

Before the end of the summer of 1914, Europe was in total war. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia; Germany declared war on Russia and France; England declared war on Germany, and voila! You have yourself a global conflict.

Upending old world orders, restructuring entire regions, and planting the seeds for future conflicts, World War I was arguably the most significant half decade in the history of the world…

Princip’s motives in assassinating Ferdinand were clear: strike a blow to the Austrian crown and incite a movement of unification for South Slavs. Little did he know that his single action would touch all corners of the world and permanently alter human civilization.

Reflecting on the vast impacts of World War I, it is striking to think the Wars’ supposed cause, the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, was largely determined by chance. It all may have been avoided if Princip never made the trip to Sarajevo in 1914; if Ferdinand took the advise of those closest to him; if Ferdinand’s driver followed the route that was assigned to him; and if Princip had stashed the gun in his coat at the cafe instead of turning it on the archduke.

I could spend the rest of my life writing about the impacts of World War I, but here I’ve focused on a few areas that represent the complexity of the conflict.

Europe

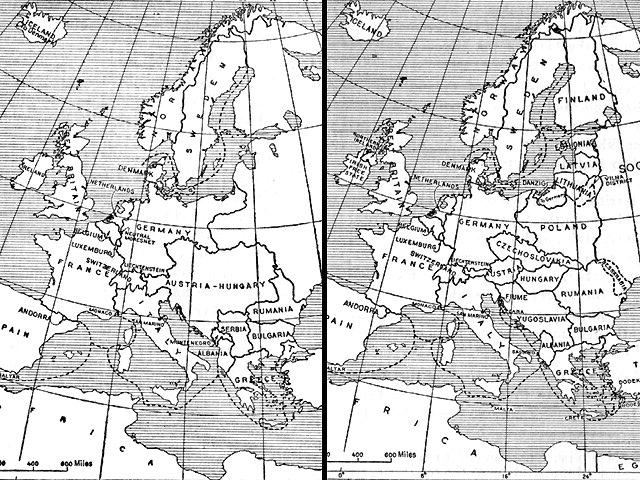

The map of Europe changed drastically after the Paris Peace Conference at the end of World War I. Decisions on future borders were appealed to and determined by the big four — Wilson (US), Lloyd George (UK), Clemanceau (France), and Orlando (Italy). As a result, the Ottoman and Hapsburg Empires were disintegrated; Germany lost land in every direction; new states were created in Yugoslavia, Czechoslavakia, Hungary, and Finland; states regained independence in Poland and Lithuania; and the vast Russian empire was embroiled in civil war.

Though peace talks after the War sought open communications, self-determination, and peaceful foundations, the opposite occurred. The interests of a few outweighed the benefit of the many and what resulted was detrimental for all. With the big four dominating peace negotiations, decisions were generally made in the best interest of their geopolitical pursuits. What resulted was growing instability in regions throughout the world, most notably, oppressive communism in Russia, violent fascism in Italy and Germany, and another world war in the matter of two decades.

Ironically, Princip’s ultimate goal in assassinating Franz Ferdinand was realized by the end of the War, though he didn’t live to experience it. With the formation of Croats, Serbs, Bosnian Serbs, and Slovenes under the nation of Yugoslavia, the unification of the South Slavic people that Princip so passionately sought was complete. However, the ethnic, cultural, and racial complexities of the region perhaps were never fully appreciated, and Yugoslavia dismembered in a series of invasions and a brutal genocide by the turn of the 21st Century.

The Middle East

Many of the modern Middle Eastern state borders are directly tied to World War I. Through back-door meetings and broken promises, France and Great Britain essentially divided Arab lands that had recently separated from a deteriorated Ottoman Empire. It was made official under the secret Sykes-Picot Agreement, which divided the Arabian Peninsula formerly governed by the Ottoman Empire into two zones that would be under the influence of the two European powers. In simple terms, Great Britain controlled Palestine, modern day Jordan and southern Iraq, while France controlled modern day Syria, Lebanon, and northern Iraq.

The significance of this diplomatic maneuver has been felt in the instability of the region for decades since the end of World War I. To be sure, the Sykes-Picot Agreement cannot solely be responsible for every conflict in the region since then, but when national borders are drawn as they were in the agreement, without input from or consideration of the peoples, cultures, religions, and customs of the region, chaos will ensue. Iraq for example, which has seemed to be in a perpetual state of turmoil since its unification in 1932, may not have such a troubled history if its regional organization after World War I respected the divides that existed between the Sunnis, Shiites, and Kurds.

What’s more, the deceptive practices of Britain and France towards the Arabs during and after World War I contributed to a schism between the West and the East that continues to this day.

The Israel-Palestine Conflict

Most people overlook the role that World War I peace negotiations had in laying the foundation for the Israel-Palestine conflict. This is because much of the negotiations, particularly the terms governing Palestinian land, were secretive.

Through the Sykes-Picot Agreement mentioned above, Britain gained administrative control of Palestine. In order to gain support of Jewish populations in the UK and abroad, as well as to consolidate power in their expected winnings in the Middle East, British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour wrote a letter, later referred to as the Balfour Declaration, to Zionist leader Lionel Walter Rothschild recognizing British support for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.”

However, the declaration conflicted with previous arrangements the British had made with the Arab world. Generally speaking, Britain had promised an independent Arab state after the War if the Arabs revolted against the Ottomans in the Middle East, which they did. Arabs made up a large majority of the 700,000 Palestinians, and hence grew weary of talks of a Jewish state in a section of their expected Arab lands.

At the time of the declaration, Jews made up less than 10 percent of Palestinian territory. As Jewish people slowly started to emigrate to Palestine with the backing of the Balfour Declaration, outbreaks of violence occurred and the seeds of cultural division were planted.

Conclusion

By the end of the War, Princip was dead, the Hapsburg monarchy had crumbled, and Woodrow Wilson was barnstorming the continent with idealistic promises of peace and prosperity for the world. The movement that Princip fought for, a united South Slavic nation, didn’t turn out as its leaders originally intended. Yugoslavia was anything but united in its brief history as Croats and Serbs never could get over their cultural differences.

Wilson’s rallying cry, a world order governed by national sovereignty and self-determination, galvanized many of those paying close attention to the actions of the leading governments after the War. Wilson spoke of a reorganization of international borders and government institutions determined by the will of the people. However, his reforms failed to fulfill their promises. The League of Nations, the staple of Wilson’s plan for international cooperation, proved ineffectual in resolving international disputes. Wilson’s Fourteen Points, a set of principles meant to arrive at fair and peaceful negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference, were routinely undermined, creating deeper resentment and division among the victors and the losers of the War. Twenty years after the Paris Peace Conference that ended World War I, Europe would again find itself in another world war that would go on to take tens of millions of more lives.

One can see how such a minor character, Gavrilo Princip, had such a major impact in world history. For that reason, it is often wondered if World War I, and as a result World War II, would have ever occurred had Princip failed to assassinate Franz Ferdinand. Many will point to the fact that Franz Ferdinand was vehemently opposed to war with Serbia because of the Russian threat and the chain reaction that would likely occur if one of the European Empires became involved. This certainly supports the notion that war could have been prevented or at least delayed if Ferdinand lived.

However, when I think of this question I am reminded of the meeting between the German Ambassador to Russia, Friedrich Pourtales, and the Russian Foreign Minster, Sergei Sazonov, just before Germany declared war on Russia in 1914. Pourtales and Sazonov were good friends at the time. Pourtales had been in Russia for several years as a German diplomat and had grown an appreciation for Russian culture. As he is prying Sazonov on Germany’s demand that Russia cease troop mobilizations against its ally Austria-Hungary, Sazonov repeatedly refuses to comply to the request, yet ensures Pourtales that Russia’s intension is not war with Germany. However, both men know that their reluctance to accept each others word means the two powers are destined for war. At Sazonov’s final refusal, Pourtales hands him the official German declaration of war, and the two old friends break down in tears. For me, the thought of two experienced foreign diplomats losing control of their emotions on the world’s largest stage perfectly illustrates how reluctant some leaders were to perpetuate the War, yet how inevitable World War I became. The combination of nationalism, regional alliances, technological advancements, militarization, and failed leadership made World War I a certainty, with or without Princip’s help.

Anecdotes aside, it is clear to see how Princip’s act was not the ultimate cause of World War I. Let’s say Princip never encounters Ferdinand outside the cafe: the original failed assassination attempt (the grenade that missed Ferdinands vehicle) would most likely still have been linked to the Serbians, which would have produced the same reaction from Austria-Hungary (an eventual declaration of war). Germany and Russia would have felt just as compelled to step in for their little brothers. In turn, France would have felt just as motivated to get involved, and the chain reaction continues…

The story of Gavrilo Princip’s assassination of Franz Ferdinand is a historical phenomenon that is maddening, intriguing, and most importantly, enlightening to our past, present, and future.

Resources:

Butcher, Tim. The Trigger: Hunting the Assassin Who Brought the World to War. New York: Grove Press. 2014.

Dedijer, Vladimir. The Road to Sarajevo. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1966.

Meyer, G.J. A World Undone. New York: Bantam Books. 2006.

MacMillan, Margaret. Paris 1919. New York: Random House. 2002.

Rogan, Eugene. Fall of the Ottomans: the Great War in the Middle East. New York: Basic Books. 2015.

Incredible peice. Did not know of the failed attempt followed by a chance siting and second chance.

LikeLike

Excellent before and after account. After the famous shots, Gavrilo Princip was swarmed by an angry mob. He was too young to be hanged, just 20 days shy of his 20th birthday. He was instead given a 20-year sentence. He died in a Bohemian prison of malnutrition and tuberculosis 4 years later at only 23, six months before the end of WWI.

LikeLike